Here are the final documents of the Holy Council

| the_documents_of_the_great_and_holy_council_2016.pdf | |

| File Size: | 848 kb |

| File Type: | |

Below is a collection of resources and texts that were collected throughout the time of the Great and Holy Council. They are, by necessity, not a complete picture.

THE GREAT AND HOLY COUNCIL OF CRETE, 2016

Day One of the Great and Holy Council

At the end of Day 1, it was leaked to the press that the first document, the Mission of the Church in Today's World' had been unanimously approved. You can read this document here

More official videos can be found here

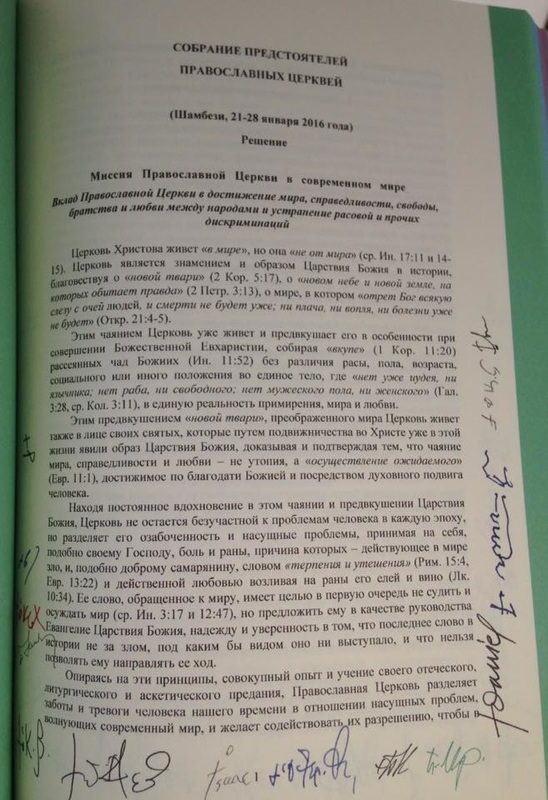

Below are photos of the Russian translation of the 'Mission in the World' document, bearing the signatures of all the Patriarchates on all the pages

Day 2 of the Great and Holy Council

On Day 1, minor amendments were introduced to the Mission document. The Delegates will vote to accept this document on Day 3. Today, on Day 2, the document on the Diaspora was discussed. The Assemblies of Bishops will continue to be a temporary measure. Beyond this, the press conference revealed little. Paul Gavriluk

ROMFEA News Agency gets it wrong

"A news report from the news agency ROMFEA.gr was issued earlier today correcting previous reports concerning the first approved text of the Council. Initially, it was reported that the changes sought by the Church of Greece were rejected by the Council's bishops and the text was approved with only minor alterations. The new report, based on a statement released from the Church of Greece, is stating that two of the three changes sought were actually approved by unanimous vote and the third was "left open for further discussion" in the near future.

With this news, a very different picture of the Council's deliberations and outcome is offered. The question is: why was the initial report so very mistaken?" Fr Peter Heers

With this news, a very different picture of the Council's deliberations and outcome is offered. The question is: why was the initial report so very mistaken?" Fr Peter Heers

Could Orthodoxy be having its first Vatican II moment?

Fr Timothy's first blog on the Council

The Mission of the Orthodox Christian Church in the world: a great and holy proclamation or a humble starting point?

Most people in the UK will have no idea about the events in Crete this week. The UK press is so full of debates and opinions about the EU and the referendum to remain or leave, or stories of rioting football fans that the high politics of international church relations gains barely a blip of notice. The second largest Christian community in the world is convening one of its most important meetings in over 300years and the UK is blissfully unaware. This is partly because one of the very problems of that this ‘second-largest community’, the Orthodox Christian Church, is facing in its meetings this week in Crete, is that it rarely speaks with one voice, and not often in a coherent and understandable manner.

I am a member of that community, I am a parish priest, but also involved in a number of international forums that discuss the issues facing the Orthodox Christian communities around the world. I am also an academic whose teaching involves the interface between faith, community and society. The meeting in Crete, called a ‘Great and Holy Council’, is going on right now and is being covered in the social media, despite a tightly controlled press office. I am not there, and I could do with a bit of the hot Cretan sunshine, and so have to work out what is going on through opinions and leaks voiced in Greek, Russian, English and French across the global media. I cannot speak with authority, but the British press have never really let the facts get in the way of a good story, and this is a good story.

The first document to be approved at this ‘great and holy Council’ is important to me. It begins to map out a way in which I might speak about the relationship between this Christian community whose history is over 2,000 years old and events and social changes that are going on right now. It’s too early to know which of these social changes, mass migration, global refugees, sexual and gender identity politics, human rights, the rise of fascism are going to still important in 300 years’ time, but parishioners and students want to know, now, how to think, speak and act on these ethical and social challenges.

But the road to that conversation with a parishioner or a student is a long and rocky one. The last of these great meetings of the Orthodox Church occurred before the rise of the philosophical and social movement of modernism that sets the context for our lives today, and the church since then has been shackled by military invasions of its spiritual heartlands in the middle east, by militant state atheism in the Soviet Union and forces of capitalism and globalisation in places like Greece. These social forces have kept the fiercely independent churches from collaborating and developing a single voice to understand the massive social changes that have occurred in that period. Let’s face it, in that time, the motorcar has been invented, digital technology has taken over everyone’s lives, the wealth of a small minority of the population has grown exponentially and new countries have emerged, and old countries have disappeared.

To speak sensibly, sensitively but in truth about any one of these massive social changes is almost impossible, and to help an individual parishioner or to teach an individual student of community and social work how to navigate the ethical challenges she faces everyday is even harder, and yet the Orthodox Christian church is proposing to speak to these issues authoritatively, in just over 4,000 words is insanely ambitious. It is also trying to do this in the context of a viciously contested process of decision-making.

Bringing together a family of 14 very different Churches, whose people have very different perspectives and life experiences, especially if they are not used to meeting and working together is an unenviable task, which is why it has taken over 50 years to get them to actually meet. The agenda for the meeting was agreed in the 1930s, but the briefing notes for the agenda (the ‘preconciliar documents’) weren’t finalised until a few months ago. Even the procedure for the meeting was argued over, who gets to sit where and how to interpret the term ‘consensus decisions’ were all fought over, and are still being debated. Most of the documents were agreed by all of the 14 Churches involved, but a few documents remained unresolved. And then, within days of the meeting, different churches dropped out. One Church had fallen out with another Church over parishes in a part of Quatar, others didn’t think that their views were going to be upheld by the consensus decision-making process and so didn’t want to attend, and another decided that because some of the others were not attending, that there was no point them going. It’s a bit like students trying to organise a pizza party.

OK, so I’m being flippant, but the absentee Churches will be important for the document that I am about to discuss. The ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ document was approved, we are told by a leaky press contingent in Crete, by the heads of 10 of the 14 Orthodox Churches, unanimously on the 20th of June 2016. Some amendments had been proposed and some approved and others rejected by the gathered leaders of the churches. I am sure that by the time this article is published the situation will have changed.

The document itself, written in Greek, translated officially into Russian and with a working copy in English, was approved by all of the delegates to the pre-Council meetings. Signatures of all 14 Patriarchs (heads of the churches) appear on the document, on every page. Even though only 10 churches have turned up for the actual Council meeting in Crete, the document has the stamp of formal approval from everyone, although commentaries have appeared in the press picking important holes in some of the ideas and expressions in the document. An example is the phrase ‘there is neither male nor female’ taken from a text in the bible known as Galatians 3:28. The paragraph in the bible is about the fact that all Christians are one before God- that our race, our sex, our gender or our civil status doesn’t matter. But those who are deeply worried that the Orthodox Christian church is about to throw out thousands of years of experience and prayer about what it is to be human think that this means that this will result in a rejection of the binary man/woman approach to gender. Another document being presented to the Council is primarily focused on marriage and gender identity; and this document about the mission of the church in the world isn’t about gender politics, but the fact this phrase is included in this text without clear qualification means the downfall of Christianity to some. One fragment of text is being torn from its context, twisted around to mean something different and thrown back at the community of faith.

The context of the document, reflecting a lot of the long term thinking and writing of Bishop John Zizoulas, a very high profile theologian who spent more than 15 years teaching in Scotland is the dignity and freedom of every human being and a commitment to promoting peace and justice to ensure that every human can flourish without discrimination. Globalisation, the increasing gap between rich and poor, the ecological degradation caused by consumerism and the loss of the sense of God in homes and communities around the world because of that secularising commitment to constant and unlimited economic growth prevent the human being from flourishing freely in the knowledge and experience of God who has created all things. For many Europeans, and certainly for sociologists like myself, this is unremarkable stuff but for Americans mired in the politics of gender-neutral toilets and public shower rooms and same-sex marriages, the dignity of the human being entails an acceptance of all of the gender identity politics of the last couple of decades. Topics such as unlimited economic growth or global climate change are either hugely contested in the USA or totally ignored in Russia. The Christians in the Middle East don’t have time to worry about consumerism or same-sex toilets when they are being bombed out of their houses or subjected to atrocities. Speaking to a globalised Christian community requires being able to accept all of the Christians where they are, in the political and social environment within which they live, and the social and ethical considerations of a Christian in Turkey is very different from one in the UK, or the middle of the USA. But beginning to develop a sense of those universal principles that unite all the Orthodox Christians in a globalised world is vitally important.

There is a long way to go. Apparently simple phrases like ‘the human person’ are to some, and I quote, “taken from the Communist Manifesto or the book "rules for Radicals" of crypto-Marxist Alinsky”. For some, discrimination and inhuman treatment of women by ignorant and ill-informed Muslim and Christian men is an everyday occurrence, for others a ‘muslim invasion’ or a communist take-over is a remote but theoretical possibility. Bridging the gap between the two, between the different experiences is going to take a lot more work than a few hundred words in a text. The text however, begins to set the context within which, in the final words of the document, Orthodox Christians can begin to reaffirm in this world today, not the worlds of ancient history, “the sacrificial love of the Crucified Lord, the only way to a world of peace, justice, freedom, and love among peoples and between nations”.

Most people in the UK will have no idea about the events in Crete this week. The UK press is so full of debates and opinions about the EU and the referendum to remain or leave, or stories of rioting football fans that the high politics of international church relations gains barely a blip of notice. The second largest Christian community in the world is convening one of its most important meetings in over 300years and the UK is blissfully unaware. This is partly because one of the very problems of that this ‘second-largest community’, the Orthodox Christian Church, is facing in its meetings this week in Crete, is that it rarely speaks with one voice, and not often in a coherent and understandable manner.

I am a member of that community, I am a parish priest, but also involved in a number of international forums that discuss the issues facing the Orthodox Christian communities around the world. I am also an academic whose teaching involves the interface between faith, community and society. The meeting in Crete, called a ‘Great and Holy Council’, is going on right now and is being covered in the social media, despite a tightly controlled press office. I am not there, and I could do with a bit of the hot Cretan sunshine, and so have to work out what is going on through opinions and leaks voiced in Greek, Russian, English and French across the global media. I cannot speak with authority, but the British press have never really let the facts get in the way of a good story, and this is a good story.

The first document to be approved at this ‘great and holy Council’ is important to me. It begins to map out a way in which I might speak about the relationship between this Christian community whose history is over 2,000 years old and events and social changes that are going on right now. It’s too early to know which of these social changes, mass migration, global refugees, sexual and gender identity politics, human rights, the rise of fascism are going to still important in 300 years’ time, but parishioners and students want to know, now, how to think, speak and act on these ethical and social challenges.

But the road to that conversation with a parishioner or a student is a long and rocky one. The last of these great meetings of the Orthodox Church occurred before the rise of the philosophical and social movement of modernism that sets the context for our lives today, and the church since then has been shackled by military invasions of its spiritual heartlands in the middle east, by militant state atheism in the Soviet Union and forces of capitalism and globalisation in places like Greece. These social forces have kept the fiercely independent churches from collaborating and developing a single voice to understand the massive social changes that have occurred in that period. Let’s face it, in that time, the motorcar has been invented, digital technology has taken over everyone’s lives, the wealth of a small minority of the population has grown exponentially and new countries have emerged, and old countries have disappeared.

To speak sensibly, sensitively but in truth about any one of these massive social changes is almost impossible, and to help an individual parishioner or to teach an individual student of community and social work how to navigate the ethical challenges she faces everyday is even harder, and yet the Orthodox Christian church is proposing to speak to these issues authoritatively, in just over 4,000 words is insanely ambitious. It is also trying to do this in the context of a viciously contested process of decision-making.

Bringing together a family of 14 very different Churches, whose people have very different perspectives and life experiences, especially if they are not used to meeting and working together is an unenviable task, which is why it has taken over 50 years to get them to actually meet. The agenda for the meeting was agreed in the 1930s, but the briefing notes for the agenda (the ‘preconciliar documents’) weren’t finalised until a few months ago. Even the procedure for the meeting was argued over, who gets to sit where and how to interpret the term ‘consensus decisions’ were all fought over, and are still being debated. Most of the documents were agreed by all of the 14 Churches involved, but a few documents remained unresolved. And then, within days of the meeting, different churches dropped out. One Church had fallen out with another Church over parishes in a part of Quatar, others didn’t think that their views were going to be upheld by the consensus decision-making process and so didn’t want to attend, and another decided that because some of the others were not attending, that there was no point them going. It’s a bit like students trying to organise a pizza party.

OK, so I’m being flippant, but the absentee Churches will be important for the document that I am about to discuss. The ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ document was approved, we are told by a leaky press contingent in Crete, by the heads of 10 of the 14 Orthodox Churches, unanimously on the 20th of June 2016. Some amendments had been proposed and some approved and others rejected by the gathered leaders of the churches. I am sure that by the time this article is published the situation will have changed.

The document itself, written in Greek, translated officially into Russian and with a working copy in English, was approved by all of the delegates to the pre-Council meetings. Signatures of all 14 Patriarchs (heads of the churches) appear on the document, on every page. Even though only 10 churches have turned up for the actual Council meeting in Crete, the document has the stamp of formal approval from everyone, although commentaries have appeared in the press picking important holes in some of the ideas and expressions in the document. An example is the phrase ‘there is neither male nor female’ taken from a text in the bible known as Galatians 3:28. The paragraph in the bible is about the fact that all Christians are one before God- that our race, our sex, our gender or our civil status doesn’t matter. But those who are deeply worried that the Orthodox Christian church is about to throw out thousands of years of experience and prayer about what it is to be human think that this means that this will result in a rejection of the binary man/woman approach to gender. Another document being presented to the Council is primarily focused on marriage and gender identity; and this document about the mission of the church in the world isn’t about gender politics, but the fact this phrase is included in this text without clear qualification means the downfall of Christianity to some. One fragment of text is being torn from its context, twisted around to mean something different and thrown back at the community of faith.

The context of the document, reflecting a lot of the long term thinking and writing of Bishop John Zizoulas, a very high profile theologian who spent more than 15 years teaching in Scotland is the dignity and freedom of every human being and a commitment to promoting peace and justice to ensure that every human can flourish without discrimination. Globalisation, the increasing gap between rich and poor, the ecological degradation caused by consumerism and the loss of the sense of God in homes and communities around the world because of that secularising commitment to constant and unlimited economic growth prevent the human being from flourishing freely in the knowledge and experience of God who has created all things. For many Europeans, and certainly for sociologists like myself, this is unremarkable stuff but for Americans mired in the politics of gender-neutral toilets and public shower rooms and same-sex marriages, the dignity of the human being entails an acceptance of all of the gender identity politics of the last couple of decades. Topics such as unlimited economic growth or global climate change are either hugely contested in the USA or totally ignored in Russia. The Christians in the Middle East don’t have time to worry about consumerism or same-sex toilets when they are being bombed out of their houses or subjected to atrocities. Speaking to a globalised Christian community requires being able to accept all of the Christians where they are, in the political and social environment within which they live, and the social and ethical considerations of a Christian in Turkey is very different from one in the UK, or the middle of the USA. But beginning to develop a sense of those universal principles that unite all the Orthodox Christians in a globalised world is vitally important.

There is a long way to go. Apparently simple phrases like ‘the human person’ are to some, and I quote, “taken from the Communist Manifesto or the book "rules for Radicals" of crypto-Marxist Alinsky”. For some, discrimination and inhuman treatment of women by ignorant and ill-informed Muslim and Christian men is an everyday occurrence, for others a ‘muslim invasion’ or a communist take-over is a remote but theoretical possibility. Bridging the gap between the two, between the different experiences is going to take a lot more work than a few hundred words in a text. The text however, begins to set the context within which, in the final words of the document, Orthodox Christians can begin to reaffirm in this world today, not the worlds of ancient history, “the sacrificial love of the Crucified Lord, the only way to a world of peace, justice, freedom, and love among peoples and between nations”.

The first document to be discussed was "The Church in the Modern World." The discussion focused on the applicability of the term "prosopon," which in theological discourse is used for the person of Christ, to human beings in the document. "Nays" came from the Church of Greece, esp. from the camp of Hieronimos Vlachos. "Yes's" came from the Ecumenical Patriarchate, especially from metropolitan Kallistos and metropolitan Zizioulas. A quick TLG search would establish that yes's are right. Since each amendment requires a unanimous endorsement of all ten delegations, each submitting one vote, the draft of the document is not very likely to be amended. Paul Gavriluk |

It would appear that unanimity is not always possible, for an obvious reason: in many disputes and disagreements, there will be two (or more) views which can't be reconciled. Sometimes they will overlap, sometimes not. In order for a Council to take action in such a case and not be paralyzed with inaction, it must be able to make a decision without unanimity. ... In such a case, the majority could be wrong, of course. If so, that would be revealed in the course of time. Fr Juvenaly Repass |

The documents are not perfect. A Response to the Pre-Conciliar Document, “The Mission of the Orthodox Church in Today’s World”

by Fr. Robert M. Arida, Susan Ashbrook Harvey, David Dunn, Maria McDowell, Teva Regule, and Bryce E. Rich

The Problem of the Diaspora was discussed but without conclusion

Day 3 of the Great and Holy Council

Day 3. In the afternoon, there was a heated discussion of the Fasting Document. The importance of different cultural contexts was emphasized. The rumour that the Council is going to abolish fasting was dispelled. Fanaticism, zealotry, and hypocricy were criticized. Paul Gavriluk

Antioch on why Antioch is not attending

Bishop Ignatius "is setting out a very restrained and moderate position, stressing that the Patriarchate of Antioch very much approved the idea of the Council and worked constructively to prepare it. He links the Patriarchate's absence in Crete strictly to the question of Qatar and not to any wider theological or ecclesiological issues, although he mentions that Antioch had a problem with the Council document on marriage. If all voices in this debate were as courteous and circumspect as this, the whole situation would be a lot easier." Bruce Clark

Fr Timothy's second blog on the Council

Chili….what? Second thoughts on the Church Council of Crete

Chiliasm. Yes, I bet you haven’t heard that in church in a month of Sundays. Chiliasm has nothing to do with a popular American meat based meal, but is in fact a theory held in early Christianity that there would be a 1,000 year reign of Jesus Christ before the end of the world. I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty here of what a ‘1,000 year reign’ might involve, but the upshot is that this theory was rejected in a Church Council in AD325 but the Church Council that is going on at the moment in Crete seems to have raised that problem again, or so some would want you to think.

The accusation of chiliasm was put by an internet blogger yesterday in one of a dozen or more forums that I have been monitoring. The gist of the argument is that the document that was discussed and approved on the first day of the Council, the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ (which I commented on here) is essentially chiliastic because of its social mission. Bear with me here, because it took me a while to figure out the link too. Chiliasm is primarily an idea that there will be a thousand years before the end of time where all evil has been conquered and good Christians will live in peace and harmony before the second coming of Jesus Christ. This notion seems to have been conflated with what theologians call the ‘social gospel’, in other words, the efforts of Christians to promote social justice, improve the social conditions of all humans, to tackle hatred and division, to improve and safeguard God’s creation.

This is the basic topic of the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ document- that all humans have personal dignity before God and that no-one should be judged or discriminated against with respect to their status or because of their gender, race etc. The blogger who accuses this document of chiliasm is presuming one of two things; that the promotion of social justice is somehow an attempt to create a ‘kingdom of God’ before the end times, and (even worse in his eyes) an attempt to create such a regime of kindness and generosity, of compassion and love, without God.

Chiliasm is associated in the minds of some with dirty words like ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’, that the social gospel is being propagated by godless communists under the guise of Christianity. Now, there may be some like that, but there are plenty of Christians who have no sense of ‘building’ a society without God, or thinking that such a society is even possible outside a deep communion with Jesus Christ. Chiliasm does not automatically equate to any discussion of social justice.

The critics even try to suggest that words such as ‘discrimination’ have no place in a Christian document like the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’. If this is the case, then pagan words like ‘homoousios’ have no place either, and therefore we cannot speak accurately about the divine human nature of Christ. Furthermore, ‘discrimination’, even if it is derived from so-called ‘socialist’ thinking, is a well understood and specific term, and does not mean that we can no longer, as Christians, discriminate or make judgements, that ‘anything goes’. What the rejection of discrimination means that that Christians should not make decisions about another person on the basis of features that are not relevant to the decision or judgement in hand. It is not legitimate to prevent a person from exercising a Christian ministry because of their sex, where the sex of that person is not relevant or a legitimate consideration. A person may not be judged as a second class Christian because they were not born of Greek or Russian families. A person may not consider themselves to be inherently Orthodox Christian because of their nationality (this is also known as the heresy of ethno-phyletism).

This brings me to the second document discussed by the Council in Crete this week, that of the ‘Church in the diaspora’. Again, this is a desperately complicated business, but ultimately a facile debate that betrays our egos and sinful weaknesses more than it proclaims the Good News of salvation in Jesus Christ.

Since the end of the soviet union, and with the onset of globalisation- an era of history where ordinary people (not just church elites) are moving in vast numbers around the world, and who are in instant communication around the world, and whose identity is no longer limited to a dozen or so miles around the village in which they were born, more and more Christians have moved outside the old territories of the Orthodox Churches, from the Greek speaking part of the Mediterranean, from the Balkans, from the Middle East under persecution, from Russia and the former Soviet Union territories. These Orthodox Christians in new lands (like the Americas) or in old Christian territories (like western Europe) have not been allowed to set up their own self-governing church structures, but instead are still connected back to ‘the old countries’. For some this is a good thing, because Christianity is a living community and we in the west should not be artificially cut off from the traditional structures and norms of those societies but on the other hand it does play into geopolitics of continuing to control the people who have left their homelands. On one hand, this arrangement whereby a parish founded by Russians outside Russia is still governed by a senior church leader back in Russia is at the same time a connection to the source of one’s Christianity, and a cultural enclave to remain and remember being Russian in a strange land, and also an extension of a greater (and for some imperialist) Russia. The same goes for Greek Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, even Serbs, Poles and Bulgarians over here because of the open movement of people as part of the European Union. You see, even the UK Referendum on the EU being voted on today (23rd June) is still relevant!

The Council in Crete comprises the representatives of 10 of the 14 independent churches from around the whole world. Some of these churches are closely associated with a particular national or cultural ‘ethne’ (Greek for people). The Church of Alexandria is a complex example- populated almost entirely by parishes from across Africa but, until recently, almost entirely staffed by Greek priests and bishops. The Moscow Patriarchate, on the other hand, is almost entirely Russian, oh and Ukrainian, because this church first started in Kiev in what is now Ukraine. It also claims China, Japan, and other post-Soviet states excluding Armenia and Georgia. On top of that, it also claims authority over any Orthodox Christian of Russian, Ukrainian, Japanese descent in places like Bentham in Gloucester and Las Vegas. This approach to church governance also applies very strongly to Romanian Orthodox Christians living in Boston, UK or Chicago, Illinois. Whilst this is wonderfully post-nationalist, and represents a global Christian community, what tends to happen is that Russians stick with Russians, and Romanians shun Greeks in these new lands, known in church circles as ‘diaspora’. We also end up having several bishops looking after their own people, all living in the same city. You get eight different bishops in Paris, all looking after their own ethnic groups. This ethnic division leads to suspicion, ethno-phyletism, racism and discrimination, and leads to some groups claiming that the Council will be abolishing the traditions of fasting for Lent, with no evidence whatsoever of this being the case. Indeed, the representatives at the Council yesterday confirmed that local differences would be considered legitimate, but that fasting is not going to be banned.

This is problem of the diaspora and lots of bishops in one city considered to be a breach of church norms and traditions. More importantly for me, it means that we do not speak as one church. We are not represented in the NHS or prison service as a single Christian body, but are related to according to national divisions, and dismissed because we considered too small to be of interest. Our mission in the world today is limited, stifled, because we talk over and around each other in different languages, replicating the tower of Babel.

Everyone in the Church agrees that this is a problem, but nobody is willing to step forward first to solve the problem. Bishops don’t want to stop being a bishop in preference of another from a different country. Nationalists and patriots don’t want to sever links with the old countries. Bishops in the old countries don’t want to lose the income from donations of their faithful overseas, especially the Churches of Constantinople-New Rome and Antioch, who have very few faithful left in their original countries, Turkey and Syria . An interim arrangement was put in place in 2009 where the different bishops in each area or city would actually begin to meet with each other regularly. This has resulted in closer relationships and exchanges of experience. It is refreshing for church leaders to meet and agree that the tiny differences in practices between the different ethnic groups are perfectly legitimate and part of the rich diversity in unity that makes up a 2,000year old global community. The Council in Crete hasn’t yet added to the existing interim arrangement of just meeting and being nice to each other, it has been quite timid in reinforcing the current temporary arrangement, but which one of them is going to be ready to vote himself out of a job? The document has been discussed, but not finalised. In the words of Rev John Chryssavigis, the spokesperson of the Council, the Council delegates are in “agreement about the establishment of canonical normality in Churches of the diaspora, but there is no unanimity among them about exactly how this should be achieved”.

Coming back to ‘chiliasm’, whilst we must be careful to ensure that social justice is not pursued for its own sake (we can leave that to the rest of society) but it must be a part of our lives as individual Christians. In the words of one of the greatest Church leaders of all time, Saint Basil the Great, “What, after all, is this hard, heavy, burdensome word which the Teacher has put forward? “Sell what you have, and give to the poor”. This clear instruction sounds like socialism, but is Christianity. Those who protest against paying taxes (state mandated theft, I hear them cry) tend not to take the words of Jesus Christ as God-mandated social justice. The message of the document ‘The Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ is not about establishing new sins where they don’t exist, but it is about recognising where our old sins have new impacts, where our selfishness and greed impacts on the environment and in global climate change, where we take advantage of modern slavery with our 99p t-shirts, where we judge people according to the colour of their skin rather because of their intentions. New problems, new contexts, new worlds , but the same old sins. Jesus Christ is the same, now and to the end of time, His Kingdom shall have no end, but we are too busy trying to build our own religions and utopias to notice.

Chiliasm. Yes, I bet you haven’t heard that in church in a month of Sundays. Chiliasm has nothing to do with a popular American meat based meal, but is in fact a theory held in early Christianity that there would be a 1,000 year reign of Jesus Christ before the end of the world. I’m not going to get into the nitty-gritty here of what a ‘1,000 year reign’ might involve, but the upshot is that this theory was rejected in a Church Council in AD325 but the Church Council that is going on at the moment in Crete seems to have raised that problem again, or so some would want you to think.

The accusation of chiliasm was put by an internet blogger yesterday in one of a dozen or more forums that I have been monitoring. The gist of the argument is that the document that was discussed and approved on the first day of the Council, the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ (which I commented on here) is essentially chiliastic because of its social mission. Bear with me here, because it took me a while to figure out the link too. Chiliasm is primarily an idea that there will be a thousand years before the end of time where all evil has been conquered and good Christians will live in peace and harmony before the second coming of Jesus Christ. This notion seems to have been conflated with what theologians call the ‘social gospel’, in other words, the efforts of Christians to promote social justice, improve the social conditions of all humans, to tackle hatred and division, to improve and safeguard God’s creation.

This is the basic topic of the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ document- that all humans have personal dignity before God and that no-one should be judged or discriminated against with respect to their status or because of their gender, race etc. The blogger who accuses this document of chiliasm is presuming one of two things; that the promotion of social justice is somehow an attempt to create a ‘kingdom of God’ before the end times, and (even worse in his eyes) an attempt to create such a regime of kindness and generosity, of compassion and love, without God.

Chiliasm is associated in the minds of some with dirty words like ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’, that the social gospel is being propagated by godless communists under the guise of Christianity. Now, there may be some like that, but there are plenty of Christians who have no sense of ‘building’ a society without God, or thinking that such a society is even possible outside a deep communion with Jesus Christ. Chiliasm does not automatically equate to any discussion of social justice.

The critics even try to suggest that words such as ‘discrimination’ have no place in a Christian document like the ‘Mission of the Church in Today’s World’. If this is the case, then pagan words like ‘homoousios’ have no place either, and therefore we cannot speak accurately about the divine human nature of Christ. Furthermore, ‘discrimination’, even if it is derived from so-called ‘socialist’ thinking, is a well understood and specific term, and does not mean that we can no longer, as Christians, discriminate or make judgements, that ‘anything goes’. What the rejection of discrimination means that that Christians should not make decisions about another person on the basis of features that are not relevant to the decision or judgement in hand. It is not legitimate to prevent a person from exercising a Christian ministry because of their sex, where the sex of that person is not relevant or a legitimate consideration. A person may not be judged as a second class Christian because they were not born of Greek or Russian families. A person may not consider themselves to be inherently Orthodox Christian because of their nationality (this is also known as the heresy of ethno-phyletism).

This brings me to the second document discussed by the Council in Crete this week, that of the ‘Church in the diaspora’. Again, this is a desperately complicated business, but ultimately a facile debate that betrays our egos and sinful weaknesses more than it proclaims the Good News of salvation in Jesus Christ.

Since the end of the soviet union, and with the onset of globalisation- an era of history where ordinary people (not just church elites) are moving in vast numbers around the world, and who are in instant communication around the world, and whose identity is no longer limited to a dozen or so miles around the village in which they were born, more and more Christians have moved outside the old territories of the Orthodox Churches, from the Greek speaking part of the Mediterranean, from the Balkans, from the Middle East under persecution, from Russia and the former Soviet Union territories. These Orthodox Christians in new lands (like the Americas) or in old Christian territories (like western Europe) have not been allowed to set up their own self-governing church structures, but instead are still connected back to ‘the old countries’. For some this is a good thing, because Christianity is a living community and we in the west should not be artificially cut off from the traditional structures and norms of those societies but on the other hand it does play into geopolitics of continuing to control the people who have left their homelands. On one hand, this arrangement whereby a parish founded by Russians outside Russia is still governed by a senior church leader back in Russia is at the same time a connection to the source of one’s Christianity, and a cultural enclave to remain and remember being Russian in a strange land, and also an extension of a greater (and for some imperialist) Russia. The same goes for Greek Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox, even Serbs, Poles and Bulgarians over here because of the open movement of people as part of the European Union. You see, even the UK Referendum on the EU being voted on today (23rd June) is still relevant!

The Council in Crete comprises the representatives of 10 of the 14 independent churches from around the whole world. Some of these churches are closely associated with a particular national or cultural ‘ethne’ (Greek for people). The Church of Alexandria is a complex example- populated almost entirely by parishes from across Africa but, until recently, almost entirely staffed by Greek priests and bishops. The Moscow Patriarchate, on the other hand, is almost entirely Russian, oh and Ukrainian, because this church first started in Kiev in what is now Ukraine. It also claims China, Japan, and other post-Soviet states excluding Armenia and Georgia. On top of that, it also claims authority over any Orthodox Christian of Russian, Ukrainian, Japanese descent in places like Bentham in Gloucester and Las Vegas. This approach to church governance also applies very strongly to Romanian Orthodox Christians living in Boston, UK or Chicago, Illinois. Whilst this is wonderfully post-nationalist, and represents a global Christian community, what tends to happen is that Russians stick with Russians, and Romanians shun Greeks in these new lands, known in church circles as ‘diaspora’. We also end up having several bishops looking after their own people, all living in the same city. You get eight different bishops in Paris, all looking after their own ethnic groups. This ethnic division leads to suspicion, ethno-phyletism, racism and discrimination, and leads to some groups claiming that the Council will be abolishing the traditions of fasting for Lent, with no evidence whatsoever of this being the case. Indeed, the representatives at the Council yesterday confirmed that local differences would be considered legitimate, but that fasting is not going to be banned.

This is problem of the diaspora and lots of bishops in one city considered to be a breach of church norms and traditions. More importantly for me, it means that we do not speak as one church. We are not represented in the NHS or prison service as a single Christian body, but are related to according to national divisions, and dismissed because we considered too small to be of interest. Our mission in the world today is limited, stifled, because we talk over and around each other in different languages, replicating the tower of Babel.

Everyone in the Church agrees that this is a problem, but nobody is willing to step forward first to solve the problem. Bishops don’t want to stop being a bishop in preference of another from a different country. Nationalists and patriots don’t want to sever links with the old countries. Bishops in the old countries don’t want to lose the income from donations of their faithful overseas, especially the Churches of Constantinople-New Rome and Antioch, who have very few faithful left in their original countries, Turkey and Syria . An interim arrangement was put in place in 2009 where the different bishops in each area or city would actually begin to meet with each other regularly. This has resulted in closer relationships and exchanges of experience. It is refreshing for church leaders to meet and agree that the tiny differences in practices between the different ethnic groups are perfectly legitimate and part of the rich diversity in unity that makes up a 2,000year old global community. The Council in Crete hasn’t yet added to the existing interim arrangement of just meeting and being nice to each other, it has been quite timid in reinforcing the current temporary arrangement, but which one of them is going to be ready to vote himself out of a job? The document has been discussed, but not finalised. In the words of Rev John Chryssavigis, the spokesperson of the Council, the Council delegates are in “agreement about the establishment of canonical normality in Churches of the diaspora, but there is no unanimity among them about exactly how this should be achieved”.

Coming back to ‘chiliasm’, whilst we must be careful to ensure that social justice is not pursued for its own sake (we can leave that to the rest of society) but it must be a part of our lives as individual Christians. In the words of one of the greatest Church leaders of all time, Saint Basil the Great, “What, after all, is this hard, heavy, burdensome word which the Teacher has put forward? “Sell what you have, and give to the poor”. This clear instruction sounds like socialism, but is Christianity. Those who protest against paying taxes (state mandated theft, I hear them cry) tend not to take the words of Jesus Christ as God-mandated social justice. The message of the document ‘The Mission of the Church in Today’s World’ is not about establishing new sins where they don’t exist, but it is about recognising where our old sins have new impacts, where our selfishness and greed impacts on the environment and in global climate change, where we take advantage of modern slavery with our 99p t-shirts, where we judge people according to the colour of their skin rather because of their intentions. New problems, new contexts, new worlds , but the same old sins. Jesus Christ is the same, now and to the end of time, His Kingdom shall have no end, but we are too busy trying to build our own religions and utopias to notice.

THE WHEEL EXCLUSIVE: GAYLE WOLOSCHAK INTERVIEWS ARCHDEACON JOHN CHRYSSAVGIS AT THE HOLY COUNCIL

The interviewer describes Archbishop Chrysostomos of New Justiniana and All Cyprus as railing against "fundamentalism" in the Orthodox Church in his remarks to the Council. The interviewer's direct quotation of him is as follows:

"The opposition of these ['fundamentalist'] groups to every notion of rapprochement with other Christians has indirectly affected even our local councils, which have attempted and continue to attempt to make profuse amendments to the texts and regulations of the documents that were prepared by the Pre-Conciliar Meetings. We have no illusions. For these groups, we have been found to be mired in heresy and apostasy." Courtney Jones

Observers from other Christian traditions at the Council

You are under no obligation to invite Presbyterians to your Parish Council, but the bishops have the freedom to invite them to attend and observe this Council. Hieromonk Ambrose

Day 4 of the Great and Holy Council

Day 4, Session 9. The discussion of the Marriage Document centered around two major issues: 1) intermarriage, or marriages of Orthodox with the non-Orthodox; 2) the second marriage of (widowed) clergy. Regarding the first issue, the prevailing view was to allow intermarriages with the non-Orthodox for the sake of mission. The hardliners, primarily the Church of Georgia, are not at the Council. The moderate position that these matters should be left for the consideration of the local churches prevailed at the first session. Regarding the second matter, only one delegate of the Serbian Church, was opposed to the second marriage of widowed clergy and the marriage of ordained (but non-tonsured) deacons. Paul Gavriluk

A perspective on the absence of the Georgian church

It seems that the document on fasting was agreed with very small amendments.

Here is the text of the working document.

Brandon Gallagher, theologian and member of the Exarchate joins others to check what the gossip on Facebook is like

Every major Council in the Church's history has one major issue or idea or product of the Conciliar process for which it is chiefly remembered, even if it dealt with a sea of topics and accomplished much else besides.

I am convinced that if this Council has the historic impact that its founders hope it to, that issue will be ecclesiology. In reality, almost every major and divisive document at the Council revolves around the subject of ecclesiology: how do Orthodox Christians in traditionally non-Orthodox countries canonically organize themselves? Can Orthodox Christians marry non-Orthodox Christians and are priests and deacons canonically permitted to pursue a second marriage? What is the relationship between the Orthodox Church and other Christian Churches, and really, more deeply, what spiritual and ecclesial realities of grace are present and active in those communities? Every topic on the agenda relates to our understanding of what the Church is and how it is meant to function, on some level. David Armstrong

What *is* ecumenicity? That a meeting was called by an emperor, or because it's provisions affect the whole household of God? Fr Timothy Curtis

Some of the reporting has been breathtakingly incorrect.

Day 5 of the Great and Holy Council

Father Timothy's third blog.

Brexit is a sin, and it’s not what you think.

Brexit is a sin, and so is autocephaly

I am supposed to be writing about the vitally important Church Council in Crete this week, but something else has happened, the UK has voted to leave the EU. I have called it a sin, and I’ll explain why. For all of you who are not Christian, bear with me, because it is still relevant. Those of you who are wanting word about the Council in Crete, I will get to that too.

For Christians, the first sin is when Adam eats an apple in the garden of Eden. For someone who is not a Christian, this is nonsense, it’s a myth. Well, as a myth it still works. Contrary to popular belief, the first sin of humanity, represented by Adam in this story from the Old Testament, is not eating an apple. That would be silly. The first since happens before that apple is eaten, before Adam commits any act, or behaves in any particular way. The first sin occurs when Adam resolves to ‘take back control’. He rejects the loving-kindness of God, which he takes for granted, and grasps self-control, autonomy and self-determination. His sin is first to be selfish, to think that he knows best and that he doesn’t have to live with the consequences of his split from God.

The same selfishness pervades the whole Brexit debate. Across all the political parties and those who are not politically affiliated I have seen over the last couple of months a debate, not about the structures of the EU, but a debate about selfishness, about taking control. This has resulted in the UK taking control of its own destiny, of becoming autonomous and self-determining. The UK has voted to leave a framework within which sovereign nation states pooled their sovereignty and gave up some of their autonomy in order to express our common humanity. Now we have given permission for everyone to ‘take back control’. Every playground bully is no free to tell a foreign kid to shove off because we have taken back control. Every greed and rapacious employer can safely dump any restrictions on working conditions because we in the UK can now determine our destiny- all laws are now up for grabs. We can even establish what we think are UK human rights. Not universal human rights, but human rights that apply to us here in the UK only. We can now free-load on the common environmental protections that reduce pollution across all our borders.

These are individual issues, and can and will be debated, but the underlying ethos will now be ‘we can decide’. The sociologist Michel Foucault theorised in the 1970s that the elites disciplined the individual to keep control of the people, and now we have seen the reaction to that, as we all (not just the brexiteers) take back control of our bodies. Instead of the elites, we as isolated individuals try to take control of our bodies, through discipline and punishment, we pierce, and mark, augment and reassign our bodies to fit our own sense of self. We seek to construct our own identity whilst at the same time trying to understand what it is to be male or female, what it is to be human, when all we know is how to be ourselves. The selfishness of adam descends into solipsism.

The brexiteers are no more sinful or selfish than the rest of us, it’s just that they have expressed their selfishness in a particular and very obvious way, but our need, our uncontrollable desire, to self-determine is now universally celebrated. We would rather be in control of our country, in control of our bodies, in control of our own identities than cede some of that control to another human being, or to God. We are so suspicious of the stranger that we have become strange to ourselves.

The debate about control and selfishness also erupted in the press and media regarding the Great and Holy Council in Crete that is happening this week. There have been discussions amongst the bishops gathered there about the Mission of the Church in Today’s World (which I commented on here) and the challenges of Orthodox Christians being scattered all over the world by war and persecution and creating a problem of the disaspora (I commented on this yesterday, but Brexit has jammed up Huffington Post’s publishing schedule, so you will have to read a draft here). Whilst the bishops went on to discuss internal issues like how much fasting we should indulge in the lead up to Christmas, the attention of the commentators shifted from the problem of the diaspora to the question of autonomy and self-governance. The discussions peaked with a debate on what actually constitutes an ‘Ecumenical Council’.

The discussion is summed up by this one comment :“In reality, almost every major and divisive document at the Council revolves around the subject of ecclesiology: how do Orthodox Christians in traditionally non-Orthodox countries canonically organize themselves?... Every topic on the agenda relates to our understanding of what the Church is and how it is meant to function, on some level.” In this statement, the commentator is really grasping at the essence of all the papers at the Holy Council, and of the debates going on in the Council chamber and across the world, and it all still boils down to self-governance, autonomy and selfishness.

Self-governance is an important principle in Orthodox Church circles. It is more accurately known as ‘autocephaly’- literally speaking ‘one-headed’ or ‘of one mind’. All the 14 churches of the world are essentially independent and self-governing. They have a head bishop, but they also have a synod or council of bishops who, between them, decide on important matters like whether Orthodox Christians can marry Roman Catholics, or whether we should eat oysters on a Friday in December. Just as importantly, they get to decide whether people who are not Orthodox Christians are even Christian or not.

In the last 300 years, this group of self-governed Churches have enjoyed, and in some cases exploited, the political situations in which they found themselves to increase that level of self-determination. The rise of nationalism meant that new self-governing churches stopped being identified by the city in which the lead bishop was located (the Patriarchate of Moscow, for example) to being identified with a whole country like the Church of Cyprus or the Church of Poland. Political strife, war, the rise of nationalism and imperialism like the Ottoman Empire and the Soviet Union meant that contact between the Churches was limited. Taking advantage of that, the self- governing churches became used to determining their own affairs and considering their own situation to be unique. In some cases, they developed a sense in which their version of Orthodox Christianity is the only true and correct Christianity. When it came to the scattering of ‘their people’ across the world as a result of these forces of war and empire, they took it upon themselves to make their own decisions about how to respond.

When, in the middle of this, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Church of Constantinople-New Rome called for a collective response, it took 50 years to devise and agree on an agenda, and finally meet this week to begin to formulate a common response to new problems. Why? Because autocephaly was taken too far. The constituent member churches of the Orthodox Church made autocephaly, the ability to govern themselves, the most important aspect of their ecclesiology. They were so concerned to distinguish themselves from the centrally governed Roman Catholic church that they neglected any real sense of conciliarity amongst themselves. Formal means of remaining in communion with the other churches were strongly maintained throughout- the churches prayed for each other, they sent each other oil of chrism as visible signs of their unity, they even celebrated the divine liturgy together as an external sign of their unity. But they didn’t get to know each other as brothers. They didn’t come together as a family in Christ.

This is beginning to change, and the heads of the Churches gathered in Crete have indicated that the most important parts of this meeting has not been the agenda, or the papers up for discussion, but for the chance to get to know each other, together. Whilst autocephaly means not being controlled by a higher bishop, like a pope or the Ecumenical Patriarch, we must be clear that autocephaly contains within it the problem of selfishness, the very sin of adam.

The Orthodox Churches must be willing to cede some of their sovereignty, to resist ‘taking back control’, to limit their freedom in order to be obedient to the gospel, especially the quote that I started the week with and repeated again to my parishioners today; that “there 'is no jew or gentile, no slave or free, nor is there male or female, for you are all one in Christ' Galatians 3:28”.

The Churches must come together to decide on what makes their decisions truly authoritative to all Orthodox Christians. There is no agenda item to decide on how decisions are made in the church. The nature of the Council is hotly contested, and this extends back into time into debates about which of the Councils in history are really ‘Ecumenical’. Some are arguing that because there is no longer a Roman emperor, no new council can ever be ecumenical, because typically emperors convened such Councils. So deciding factor on whether a Council is binding on the whole church depends on whether a civil authority like the Emperor convoked the council, not whether the council spoke the truth. Others argue that Councils are ecumenical because their decisions are important to the whole church (rather than local issues) and because they have been received as authoritative by all the churches. Some argue that there will only ever be seven ecumenical councils, convened by an Emperor. Others argue that there are more councils (like the 4th and 5th Councils of Constantinople in 879–880 and 1341–1351, the Synod of Iasi, Romania in 1642 and the Synod of Jerusalem in 1672). Some argue that any Council that does not discuss ‘dogma’, i.e. vital questions of who God and Jesus are, cannot be ecumenical. Others would consider that the first, Apostolic Council of Jerusalem, that decided that the good news of Jesus Christ could be preached to non-Jews is not an ecumenical council.

This complicated picture means that the process by which we act as a church, in which we decide which issues are vitally important and affect the whole world, which ones only affect the know Roman imperial world (one way of defining the word ecumenical) or which ones affect the whole household of God (another way of defining the word ecumenical). Without that, the separate Orthodox Churches are just that, separate. They are subject to the sin of selfishness; they can be tempted to ‘take back control’. They retain the power to decide how to decide. We don’t need centralised power to resolve this problem, we need conciliarity. We need for the churches to cede some of their power to the Council of the Patriarchs. This may begin to happen.

In the UK, however, we have withdrawn from conciliarity. We have withdrawn from the Council of European States. We are in the process of walking away from the difficult business of living with our neighbours and are preparing instead to treat them as ‘jews and gentiles’ as separate peoples. We are repeating again the sin of adam in demanding self-control. We are repeating the first sin of selfishness.

Brexit is a sin, and so is autocephaly

I am supposed to be writing about the vitally important Church Council in Crete this week, but something else has happened, the UK has voted to leave the EU. I have called it a sin, and I’ll explain why. For all of you who are not Christian, bear with me, because it is still relevant. Those of you who are wanting word about the Council in Crete, I will get to that too.

For Christians, the first sin is when Adam eats an apple in the garden of Eden. For someone who is not a Christian, this is nonsense, it’s a myth. Well, as a myth it still works. Contrary to popular belief, the first sin of humanity, represented by Adam in this story from the Old Testament, is not eating an apple. That would be silly. The first since happens before that apple is eaten, before Adam commits any act, or behaves in any particular way. The first sin occurs when Adam resolves to ‘take back control’. He rejects the loving-kindness of God, which he takes for granted, and grasps self-control, autonomy and self-determination. His sin is first to be selfish, to think that he knows best and that he doesn’t have to live with the consequences of his split from God.

The same selfishness pervades the whole Brexit debate. Across all the political parties and those who are not politically affiliated I have seen over the last couple of months a debate, not about the structures of the EU, but a debate about selfishness, about taking control. This has resulted in the UK taking control of its own destiny, of becoming autonomous and self-determining. The UK has voted to leave a framework within which sovereign nation states pooled their sovereignty and gave up some of their autonomy in order to express our common humanity. Now we have given permission for everyone to ‘take back control’. Every playground bully is no free to tell a foreign kid to shove off because we have taken back control. Every greed and rapacious employer can safely dump any restrictions on working conditions because we in the UK can now determine our destiny- all laws are now up for grabs. We can even establish what we think are UK human rights. Not universal human rights, but human rights that apply to us here in the UK only. We can now free-load on the common environmental protections that reduce pollution across all our borders.

These are individual issues, and can and will be debated, but the underlying ethos will now be ‘we can decide’. The sociologist Michel Foucault theorised in the 1970s that the elites disciplined the individual to keep control of the people, and now we have seen the reaction to that, as we all (not just the brexiteers) take back control of our bodies. Instead of the elites, we as isolated individuals try to take control of our bodies, through discipline and punishment, we pierce, and mark, augment and reassign our bodies to fit our own sense of self. We seek to construct our own identity whilst at the same time trying to understand what it is to be male or female, what it is to be human, when all we know is how to be ourselves. The selfishness of adam descends into solipsism.

The brexiteers are no more sinful or selfish than the rest of us, it’s just that they have expressed their selfishness in a particular and very obvious way, but our need, our uncontrollable desire, to self-determine is now universally celebrated. We would rather be in control of our country, in control of our bodies, in control of our own identities than cede some of that control to another human being, or to God. We are so suspicious of the stranger that we have become strange to ourselves.

The debate about control and selfishness also erupted in the press and media regarding the Great and Holy Council in Crete that is happening this week. There have been discussions amongst the bishops gathered there about the Mission of the Church in Today’s World (which I commented on here) and the challenges of Orthodox Christians being scattered all over the world by war and persecution and creating a problem of the disaspora (I commented on this yesterday, but Brexit has jammed up Huffington Post’s publishing schedule, so you will have to read a draft here). Whilst the bishops went on to discuss internal issues like how much fasting we should indulge in the lead up to Christmas, the attention of the commentators shifted from the problem of the diaspora to the question of autonomy and self-governance. The discussions peaked with a debate on what actually constitutes an ‘Ecumenical Council’.

The discussion is summed up by this one comment :“In reality, almost every major and divisive document at the Council revolves around the subject of ecclesiology: how do Orthodox Christians in traditionally non-Orthodox countries canonically organize themselves?... Every topic on the agenda relates to our understanding of what the Church is and how it is meant to function, on some level.” In this statement, the commentator is really grasping at the essence of all the papers at the Holy Council, and of the debates going on in the Council chamber and across the world, and it all still boils down to self-governance, autonomy and selfishness.

Self-governance is an important principle in Orthodox Church circles. It is more accurately known as ‘autocephaly’- literally speaking ‘one-headed’ or ‘of one mind’. All the 14 churches of the world are essentially independent and self-governing. They have a head bishop, but they also have a synod or council of bishops who, between them, decide on important matters like whether Orthodox Christians can marry Roman Catholics, or whether we should eat oysters on a Friday in December. Just as importantly, they get to decide whether people who are not Orthodox Christians are even Christian or not.

In the last 300 years, this group of self-governed Churches have enjoyed, and in some cases exploited, the political situations in which they found themselves to increase that level of self-determination. The rise of nationalism meant that new self-governing churches stopped being identified by the city in which the lead bishop was located (the Patriarchate of Moscow, for example) to being identified with a whole country like the Church of Cyprus or the Church of Poland. Political strife, war, the rise of nationalism and imperialism like the Ottoman Empire and the Soviet Union meant that contact between the Churches was limited. Taking advantage of that, the self- governing churches became used to determining their own affairs and considering their own situation to be unique. In some cases, they developed a sense in which their version of Orthodox Christianity is the only true and correct Christianity. When it came to the scattering of ‘their people’ across the world as a result of these forces of war and empire, they took it upon themselves to make their own decisions about how to respond.

When, in the middle of this, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Church of Constantinople-New Rome called for a collective response, it took 50 years to devise and agree on an agenda, and finally meet this week to begin to formulate a common response to new problems. Why? Because autocephaly was taken too far. The constituent member churches of the Orthodox Church made autocephaly, the ability to govern themselves, the most important aspect of their ecclesiology. They were so concerned to distinguish themselves from the centrally governed Roman Catholic church that they neglected any real sense of conciliarity amongst themselves. Formal means of remaining in communion with the other churches were strongly maintained throughout- the churches prayed for each other, they sent each other oil of chrism as visible signs of their unity, they even celebrated the divine liturgy together as an external sign of their unity. But they didn’t get to know each other as brothers. They didn’t come together as a family in Christ.

This is beginning to change, and the heads of the Churches gathered in Crete have indicated that the most important parts of this meeting has not been the agenda, or the papers up for discussion, but for the chance to get to know each other, together. Whilst autocephaly means not being controlled by a higher bishop, like a pope or the Ecumenical Patriarch, we must be clear that autocephaly contains within it the problem of selfishness, the very sin of adam.

The Orthodox Churches must be willing to cede some of their sovereignty, to resist ‘taking back control’, to limit their freedom in order to be obedient to the gospel, especially the quote that I started the week with and repeated again to my parishioners today; that “there 'is no jew or gentile, no slave or free, nor is there male or female, for you are all one in Christ' Galatians 3:28”.

The Churches must come together to decide on what makes their decisions truly authoritative to all Orthodox Christians. There is no agenda item to decide on how decisions are made in the church. The nature of the Council is hotly contested, and this extends back into time into debates about which of the Councils in history are really ‘Ecumenical’. Some are arguing that because there is no longer a Roman emperor, no new council can ever be ecumenical, because typically emperors convened such Councils. So deciding factor on whether a Council is binding on the whole church depends on whether a civil authority like the Emperor convoked the council, not whether the council spoke the truth. Others argue that Councils are ecumenical because their decisions are important to the whole church (rather than local issues) and because they have been received as authoritative by all the churches. Some argue that there will only ever be seven ecumenical councils, convened by an Emperor. Others argue that there are more councils (like the 4th and 5th Councils of Constantinople in 879–880 and 1341–1351, the Synod of Iasi, Romania in 1642 and the Synod of Jerusalem in 1672). Some argue that any Council that does not discuss ‘dogma’, i.e. vital questions of who God and Jesus are, cannot be ecumenical. Others would consider that the first, Apostolic Council of Jerusalem, that decided that the good news of Jesus Christ could be preached to non-Jews is not an ecumenical council.

This complicated picture means that the process by which we act as a church, in which we decide which issues are vitally important and affect the whole world, which ones only affect the know Roman imperial world (one way of defining the word ecumenical) or which ones affect the whole household of God (another way of defining the word ecumenical). Without that, the separate Orthodox Churches are just that, separate. They are subject to the sin of selfishness; they can be tempted to ‘take back control’. They retain the power to decide how to decide. We don’t need centralised power to resolve this problem, we need conciliarity. We need for the churches to cede some of their power to the Council of the Patriarchs. This may begin to happen.

In the UK, however, we have withdrawn from conciliarity. We have withdrawn from the Council of European States. We are in the process of walking away from the difficult business of living with our neighbours and are preparing instead to treat them as ‘jews and gentiles’ as separate peoples. We are repeating again the sin of adam in demanding self-control. We are repeating the first sin of selfishness.